Dissertation UK Example: Consumers’ perceptions of rental fashion in UK

Introduction

This chapter provides background information to the issue under research study as well as the research process. In this respect, the subject under investigation is the consumers’ perceptions of rental fashion in the UK. Similarly, the research question, as well as objectives, are also outlined in the chapter.

-

- Background

In contemporary times, the sharing economy is evident in accommodation, travel, food, and, most recently, fashion. Apart from using cloth renting stores, consumers in the UK purchase most of their clothes through online shopping or e-commerce sites (Scuotto et al., 2017). For copious consumers, online shopping is viewed as convenient and time-saving. Moreover, these consumers can compare the products and prices of various suppliers to have the best offers. As a result of comparing the best products and prices, there is higher anticipation of fashionable clothes. According to Brydges et al. (2018), it is apparent that clothe renting is currently changing the development of UK’s fashion industry because many people are accepting the notion of replacing buying with renting. Presently, rental fashion in the country is dominated by the dance and wedding stores, which offer rental services to their customers when they need to participate in momentous occasions such as banquets. However, according to Scuotto et al. (2017), consumer trends tend to be dynamic because of the nature of the fashion industry, which is never static. Yang et al. (2017) point out that many consumers agree that renting offers the latest fashion at a price that is relatively low compared to buying, making it attractive. As such, the best mode of advertising to these consumers relative to rental fashion has been fashion-related websites and magazines. Therefore, the benefits of rental fashion, as seen above, are attributed to a variety of choices and affordable price.

According to Clube and Tennant (2020), the key reason for the continued growth of fashion renting is because of the change in consumer perceptions. As such, cloth renting needs customers to re-evaluate how they use, dispose of and care for clothing, which denotes that they must form new skills and consumption patterns. Even though many studies have documented various reasons why consumers have hesitated in the adoption of rental fashion, Cavender et al. (2020) discovered that perceived barriers and benefits are mainly context-specific. For example, unlike rental fashion, in the traditional fashion industry, consumers can buy clothes anytime and anywhere after being posted either online or in physical shops. However, the rental fashion market has new implications for consumption because renting clothes needs a different kind of consumption. For instance, according to Cavender et al. (2020), consumers always need to wait, especially for luxury clothes, for their chance to wear such clothes in cases where they are limited. This issue presents an inconvenience, which is unfamiliar to the traditional fashion system leading to negative customer perception of renting fashion. Many consumers also perceive increased waiting time and lack of availability as significant barriers, which requires changes in the current shopping behaviour of consumers (Brydges et al., 2018). Some fashion consumers also view cloth rental negatively because of ownership issues. Unlike bought clothes, rented ones make the consumers ensure that they are in good condition and also returned based on the agreed time, which makes clothing ‘ownership” to be collective instead of individual experience.

Non-ownership of various fashion products has been perceived as a common concern of consumers, especially in the UK. According to Capone and Lazzeretti (2016), consumers perceive that renting does not offer equal gratification as owning a product in actuality or being in a position to afford it. Ostensibly, materialistic consumers commonly ascribe value to ownership. Therefore, they perceive non-ownership to be unattractive and, in most cases, not a viable option for them. Most of the consumers who are in support of rentals agree that rental is mainly suitable in cases where the needs can relatively change quickly, such as wedding occasions, among others. Apart from functional barriers, renting clothes can eliminate the hedonistic facets of shopping (Capone and Lazzeretti, 2016). Even though either offline or online fashion services dealing with rentals can easily replicate the hedonistic shopping aspect, both of them form a novel user experience. Other barriers identified in most studies are garment hygiene, quality, and maintenance issues. These facets are associated with trust in the rented brand, which is primarily influenced by the theory of social capital (Pedersen, Gwozdz, and Hvass, 2018). The social capital theory views behavioural intention and consumer’s perceptions to be impacted by an organisational trust. Thus, companies with questionable operations and staff cannot be successful in the fashion renting business because of negative customer perception about them. Another attitude that hinders cloth renting industry from growing is the perceived cost. Many consumers perceive the concept of paying continuously for services without obtaining ownership as expensive and risky (Kwon and Choo, 2020). Some also posited that rental fashion turns consumption of fashion into monetary obligation, which affects their finances negatively. Despite the negative perceptions of some consumers, many perceive rental fashion positively.

According to Kwon and Choo (2020), some consumers see the advantages of using fashion rentals compared to buying. Remarkably, conferring to Poorthuis et al. (2020), renting a wardrobe permits customers to change regularly their look by trying new things and staying on-trend. It also allows many consumers to attain their newness needs in a manner that is considered effective because it permits them to indulge in the fast trend of fashion with few consequences (Pedersen et al., 2018). The main reason is that luxurious clothes can be rented and used at a fraction of their value relative to their retailing cost, which makes luxurious products affordable. Nevertheless, for the consumers who are for rentals clothes, they expect transparency at any given time (Kwon and Choo, 2020). For example, they need to have more data regarding the provenience of the products and the quality of used materials. Customers, in particular, those who are environmentally conscious, prefer to have products that do not impact the environment negatively (Bick et al., 2018). As such, numerous brands dealing in renting fashion are reacting to these requirements raised from their business demand side by being as transparent as they can in their operations.

-

- Research gaps

The increased globalisation pace in the business world has led to sophistication and a wide variety of choices in fashion. As such, Pedersen et al. (2018) point out that consumers are now having a wide range of options to make concerning their clothing. Based on these studies, the current trend that is gaining traction in the fashion industry mainly is garment renting (Bick et al., 2018; Kwon and Choo, 2020). However, there are scant studies that cover this issue in detail, as seen above. The few studies that talk about rental fashion addressed it relative to traditional fashion. Apart from that, despite most studies agreeing that customer’s perceptions are imperious in fashion renting, Capone and Lazzeretti (2016) point out that none of them has evaluated the impacts of customer perception in one study. Also, most present studies on renting accentuate on car renting and fashion renting with only a few on clothes renting in which it is covered lightly, without any focus on the UK market. According to past studies, consumer’s perception of renting fashion can be applied in adjusting marketing strategies to increase the revenue of cloth renting business. According to Capone and Lazzeretti (2016), it is necessary to know consumers’ perceptions in a new model of business, which determines whether they will accept the business or not. For these reasons, the decision about the perception of consumers in fashion renting is essential, which is the principal motive of the study.

-

- Aim of the research

The research study aims at looking at the attitudes of consumers in the UK towards rental fashion and any perceived risk involved.

-

- Research objectives

- To understand how attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioural control of UK consumers affect their perceptions and intentions to use rental fashion services.

- To examine the perceived risks which prevent UK consumers from renting fashion items.

- Research contributions

This research will benefit specifically those who are interested in venturing into rental fashion in different parts of the world. It will help them in forming their business strategies based on the findings of this study regarding customers’ perception of retail fashion. Subsequently, the findings will assist stakeholders in the fashion industry to understand some of the key factors contributing to the preferences of most apparels that can help in their business growth despite the surging competition in the sector. It will also have implications for both developing and developed nations’ governments such as the UK and other policymakers who aim to establish competency in the growing market of rental fashion. Apart from that, this study will contribute to the growing literature associated with consumer perception, patronage, and attitude towards renting fashion. Some of the theoretical contributions will be made on consumer perception with respect to rental fashion because the existing theories mainly concentrate on general fashion. This study mainly has implications on the subsect of perception theory known as self-perception theory because rental fashion, as seen from the findings, is primarily concerned with the perception of individuals.

-

- Dissertation outline

The section provides a brief overview of this dissertation’s chapters, indicating its general structure. Background information of the research, the research question and objectives, are outlined in the introduction. Chapter one is the sector overview, in which an analysis of the fashion industry has been conducted. Chapter two is the marketing theories. A detailed analysis of past studies has been conducted, and the used concepts are also defined in this section. Chapter three shows the conceptual development based on the findings of literature review. Chapter four is the methodology. The selected research methods, approaches, strategies, research process, collection of data, as well as ethical concerns are presented. Chapter five is the findings and discussions. The results from the collected data are presented. This chapter entails a discussion of the findings and analysis to establish an objective conclusion. As such, the final chapter is the conclusion in which the analysed information from the research is summarised. The recommendations are also provided in the chapter together with direction for future studies.

Chapter One: Literature Review I – Industry/Sector Overview

2.1 Introduction

This chapter introduces a literature overview of the industry/sector which is related to this research. It covers an overview of the fashion industry and rental fashion sector in the UK, as well as the latest issues and current trends. This chapter provides a better understanding of where this research is conducted.

2.2 Fashion industry in the UK

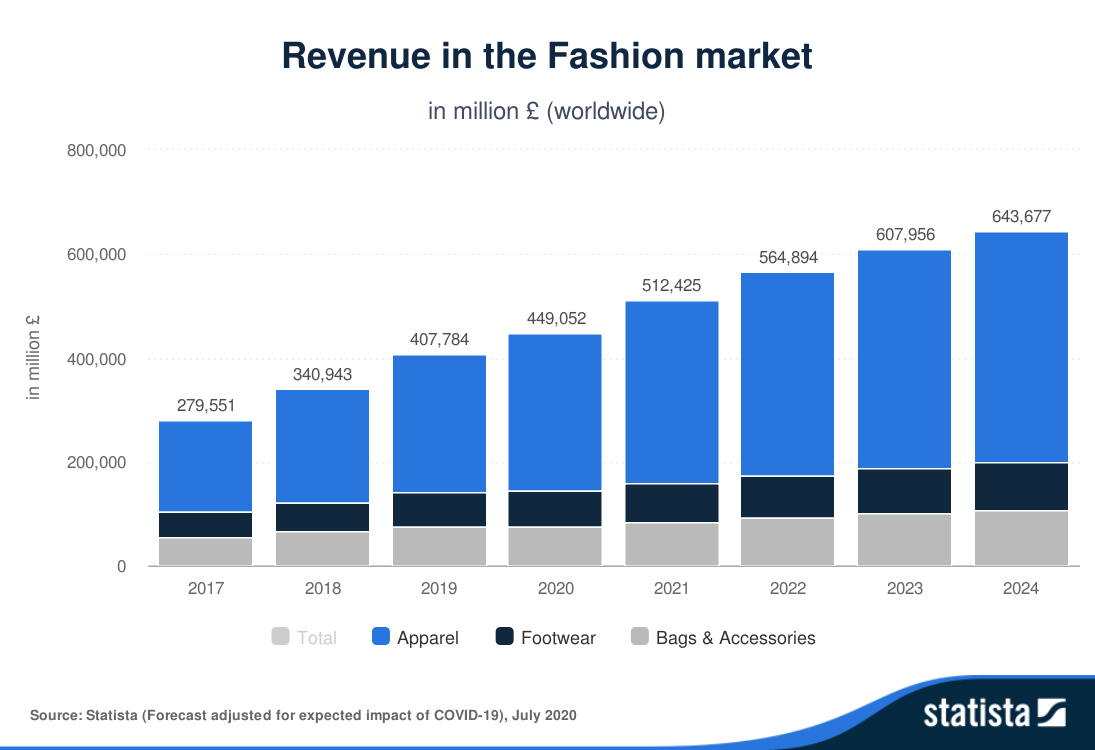

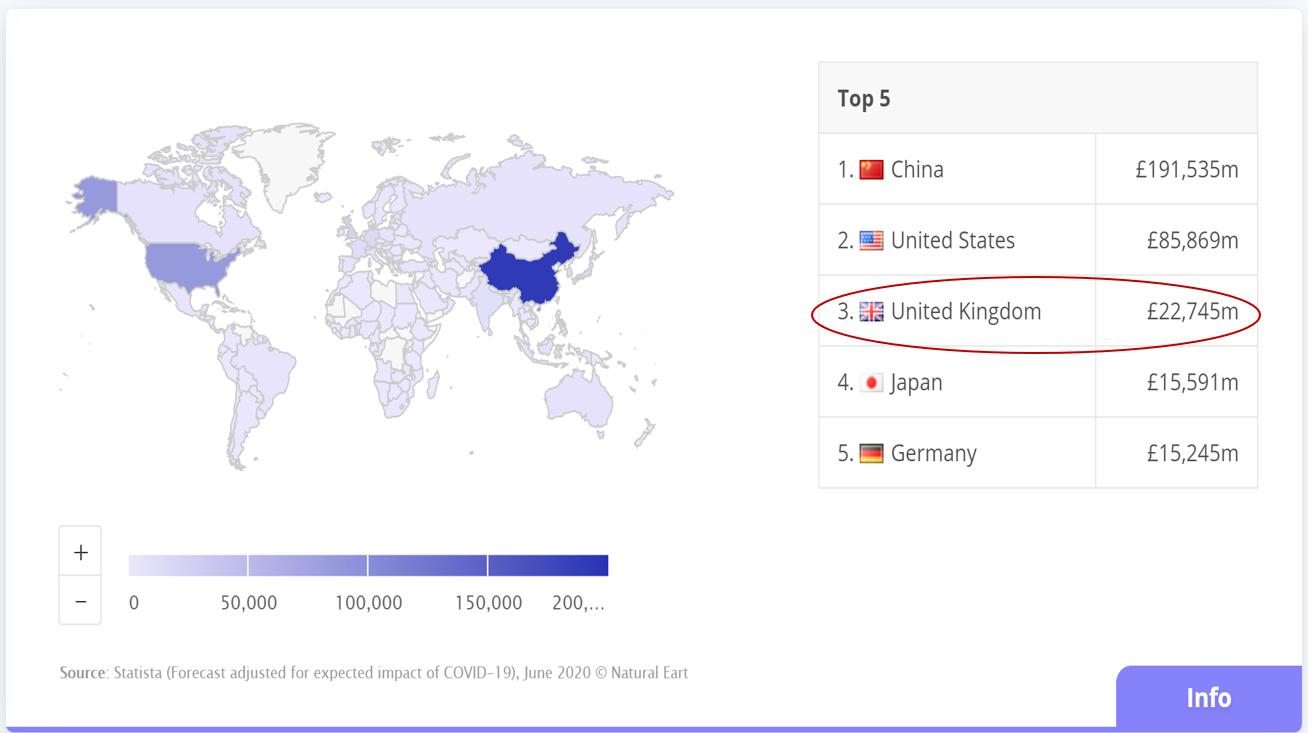

Fashion is one of the largest industries in the world. According to the latest forecast by Statista (2020), the global revenue of the fashion industry will reach £449,052m in 2020 and £643,677m by 2024 (see Figure 1). The industry plays a significant role in the UK as the country ranked the third in terms of the market volume (see Figure 2) (Statista, 2020). Report from WRAP (2017) shows that the clothing consumed in the UK has increased from 1,030,000 tonnes in 2010 to 1,130,000 tonnes in 2016.

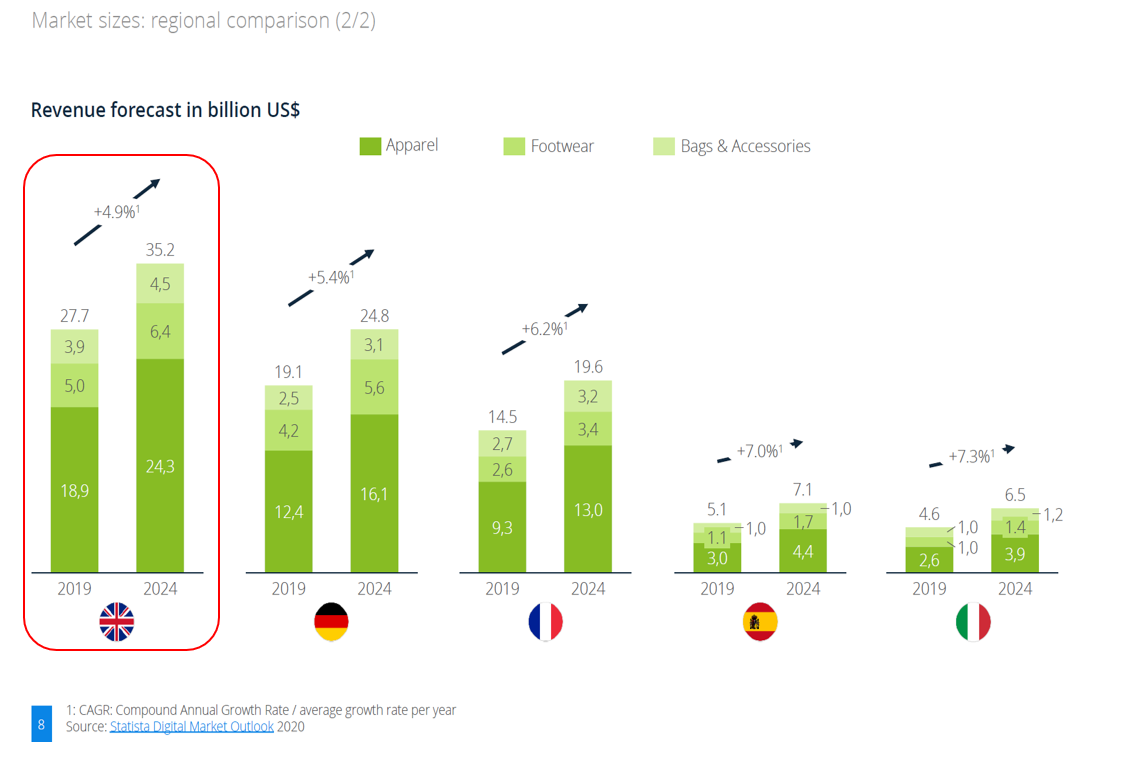

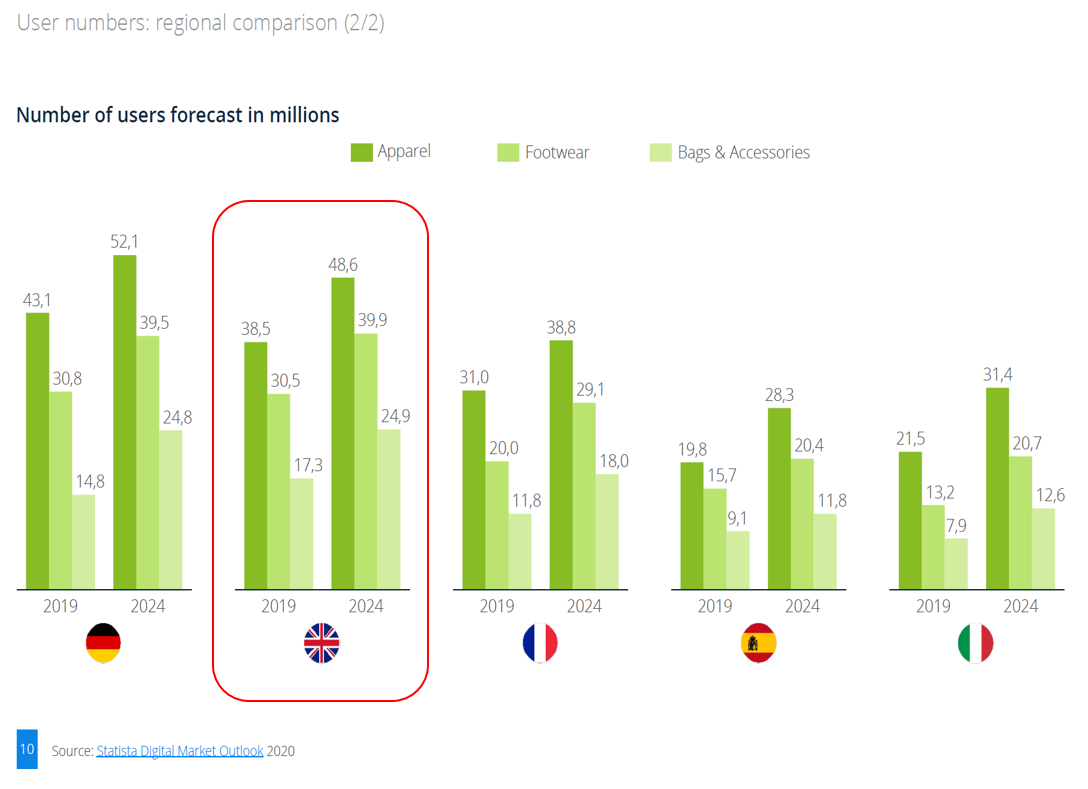

Fashion has contributed £32 billion to the UK economy, and has provided nearly 900,000 jobs across the country (Sleigh, 2018). Fashion companies launch more collections every year. For example, Zara and H&M have produced 24 and 12 collections annually respectively (McFall-Johnsen, 2019), which also encourages consumers to purchase more fashion items. A report from Statista (2020) also shows that the UK is the largest online fashion market (see Figure 3) and has the most online fashion users (see Figure 4) in Europe. However, the fashion industry has led to concerns over plastic and water pollution, labour abuses, textile waste and overproduction among consumers. Reports from Mistra Future Fashion Consortium (2015) and House of Commons (2019) indicate that fast-fashion to be blamed for these environmental impacts. Fast-fashion is a clothing supply chain model which aims at renewing the fashion products in stores in order to react rapidly to the latest fashion trends and consumers’ demands (Byun and Sternquist, 2011). As stated in the report of YouGov (2020), women who aged between 18 and 24 in the UK are more keen on fast-fashion and tend to spend more on clothing. A survey from management consulting company, McKinsey & Company (2019) found out that one in three British young women see clothes as old after one or two usage. According to The World Bank statistics (2019), 93 billion cubic meters of water are used and a half of million tons of plastic microfibers are thrown away to the ocean every year. Fabric dyeing produces nearly 20% of wastewater. Fashion production also accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions, which is higher than that of international flights and shipping. Based on the statistics from WRAP (2020), around 350,000 tonnes of used garments are sent to landfill every year across the country. Therefore, more consumers are looking for sustainable and ethical fashion.

Figure 2.1: Revenue in the fashion market (worldwide)

(Source: Statista, 2020)

Figure 2.2: Revenue in the fashion market – Global comparison

(Source: Statista, 2020)

Figure 2.3: Revenue of online fashion market in Europe

(Source: Statista, 2020)

Figure 2.4: Online fashion market users in Europe

(Source: Statista, 2020)

2.3 Current trends in the fashion industry

Sustainability is not a new topic in the context of fashion. There are several ways to be sustainable in fashion, such as clothes donation, repairing fashion, and second-hand clothing. Mintel report (2019a) points out that 30% of British consumers state that they would be more willing to shop from a retailer if it sells sustainable fashion items. More fashion retailers have launched sustainable fashion ranges, such as JoinLife by Zara and Conscious by H&M. A latest report released by McKinsey & Company (2020), suggests that sustainability measures and materials revolution as two of the main themes for the fashion industry in 2020.

Access-based consumption is defined by Lee and Chow (2020) as “the peer-to-peer sharing of underutilized products and services”. Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012) identified it as the “transactions that can be market mediated but where no transfer of ownership takes place” (p.881). Access-based consumption is gaining a higher popularity in different contexts such as music streaming (Sportify), sharing of car (Uber/Zipcar) and accommodation (Airbnb). Rental business model is one of the examples of access-based consumption. An early study by Durgee and O’Connor (1995) revealed that renting is linked with freedom, non-commitment and a prevention from maintenance tasks. Gumulya and Ginting (2020) further point out that renting allows consumers to enjoy a product without the concern of purchasing, maintaining and storing. It also helps to reduce the problems when a product reaches its lifespan. As stated in the report of WRAP (2012), environmental impacts of water waste and carbon footprints can be reduced if the clothing life is extended by only nine months. The idea of rental fashion is emerging in the fashion industry, which is perceived as an alternative of fast-fashion and a more sustainable option. A recent study conducted by Lang et al. (2020) points out that, four main benefits of rental fashion are experiential value, financial value, ease of use and utilitarian value. The authors suggest that consumers are beneficial from having the high-end fashion experience with a cheaper price. Lang (2018) also indicates that rental fashion can be viewed as treasure hunting, which can meet consumers’ aesthetic needs.

According to The Allied Market Research (2017), it is estimated that the global online clothing rental market to reach US$1,856 million (approximately £1,472 million) by 2023. As stated in the Grand View Research (2019), North America was the market leader and occupied nearly 40% of the market share globally in 2018. In particular, the US has contributed most of the share. Europe occupied around 27% of the market share, which is the second-largest segment. Western Europe is the biggest segment in Europe, as consumers tend to have a higher purchasing power and are more fashion conscious in countries such as France, Italy and the UK.

2.4 Rental fashion in the UK

GlobalData has forecasted that the net worth of the UK clothing rental market will reach £2.3 billion by 2029 (Independent, 2020). Some of the clothing renting platforms in the UK are Hurr Collective, My Wardrobe HQ and Girl Meets Dress. High Street brand, H&M, had also trialled rental service in Stockholm (Mintel 2019b). Rental fashion is not a new idea and has well developed in the US, which accounts for £2 billion to the economy a year (The Telegraph, 2019). However, this concept is still at its beginning stage in the UK.

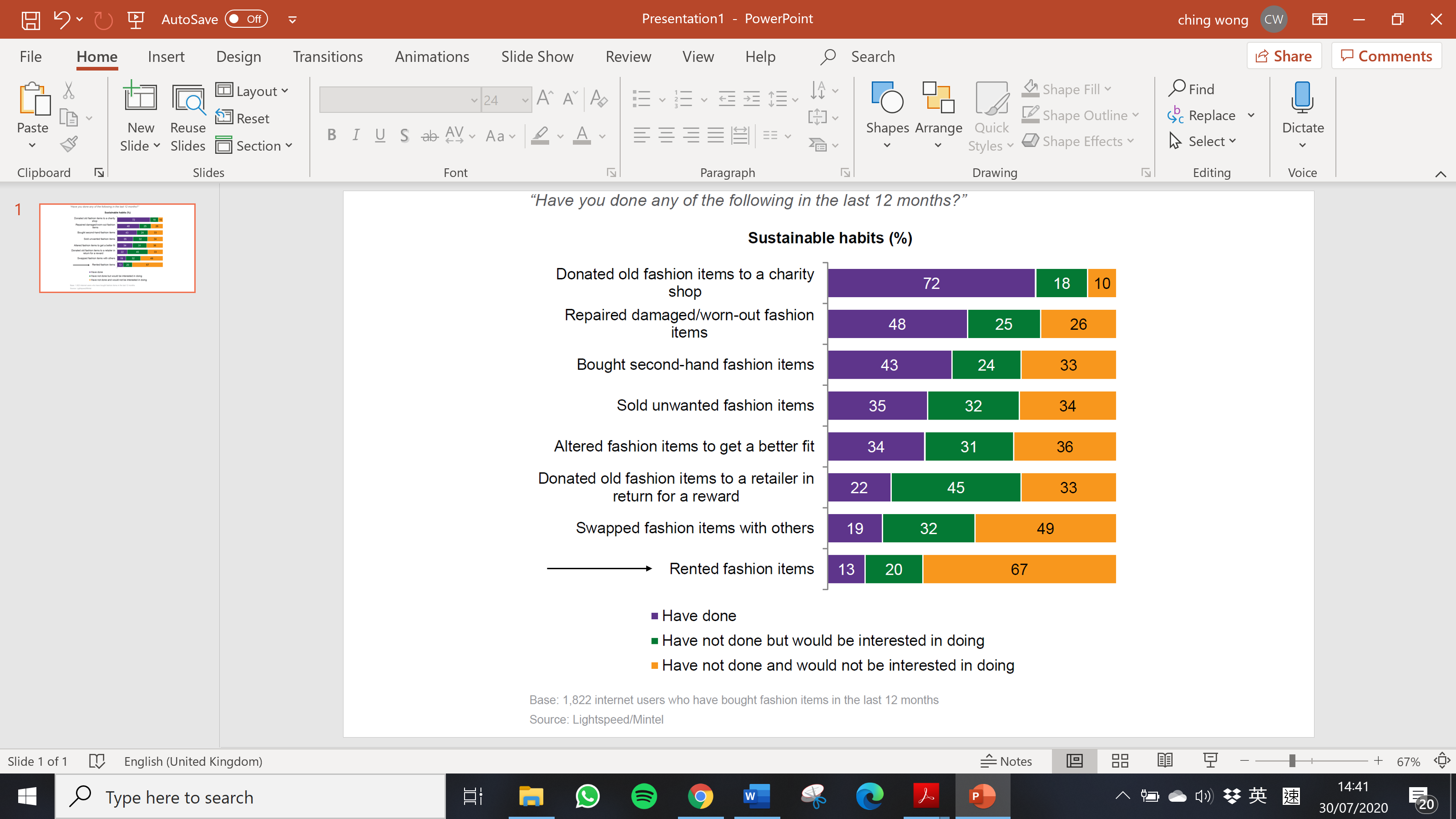

A survey conducted by professional services firm KPMG (2019), reveals that only 2% of British consumers link rental services to sustainable fashion. It has shown majority of UK consumers are not aware of rental fashion services. In terms of consumers’ willingness of renting clothes, according to the report from GlobalData Retail (2019), up to 84% of consumers are not likely to rent clothes or accessories, and 56% of consumers prefer to own their fashion items. Research from Mintel (2019a) indicates that majority of consumers would not be interested in renting fashion items (67%), while clothes donation and repaired fashion are in a higher popularity (see Figure 5).

Figure 2.5: Sustainable behaviours towards fashion, June 2019

(Source: Mintel, 2019a)

2.5 Summary

This chapter presents the overview of the fashion industry, issues of sustainability and rental fashion sector in the UK. Fashion industry is one of British largest industries. But at the same time, concerns over pollutions and wastes arouse. Consumers are more aware of being sustainable when buying fashion items. Rental fashion may not be a popular sustainable or ethical option in the UK. As consumers are more willing to donate or repair their fashion items, instead of renting them.

Chapter Two: Literature Review II

-

- Introduction

This chapter presents a range of literature regarding the marketing theories adopted in this research. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) will be used as the framework of the research. The three determinants of the theory, as well as perceived risks involving in one’s attitudes are discussed. This chapter also builds the conceptual framework of this research, which is in the next chapter – conceptual development.

3.2 AIDA Model

The AIDA model was introduced by E. St. Elmo Lewis in 1898, as cited in Pashootanizadeh and Khalilian, 2018. It is a theory of communication. AIDA refers to Attention, Interest, Desire and Action. According to Michaelson and Stacks (2011), the AIDA model has described the four cognitive phases encountered by an individual when purchasing new products or accepting new ideas. Kotler et al. (2016) define the function of marketing as “identifying and meeting human and social needs at a profit” (p.6). According to the needs of the model, Hadiyati (2016) states that the objective of marketing is to draw the attention of the potential consumers, to raise their interest and desire and finally to act (i.e. to purchase the product or service). It also shows the importance of the model in nowadays marketing practice. The model is widely used in the marketing activities (Michaelson and Stacks, 2011; Hassan et al., 2015; Hadiyati, 2016; Pashootanizadeh and Khalilian, 2018; Cheah et al., 2019). Since rental fashion is not commonly known in the UK, the AIDA model will be useful for marketers to identify when and how to engage and communicate with consumers at each of the stages. Thus, the aim is to encourage consumers to act, which is to use rental fashion services.

3.3 The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) was developed to examine behavioural intentions. Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) propose that an individual’s intention to perform a behaviour is a function of one’s attitude toward the behaviour and subjective norms. A behavioural intention refers to the extent of how likely an individual will perform a behaviour in a certain way, whether he/she will do it eventually. According to the theory, the intentions of using rental fashion services illustrates the extent of consumers’ willingness to rent fashion items or adopt sustainable options. Ajzen (1985) proposes that attitude and subjective norms have a notable positive relationship with the behavioural intention. The theory has been applied by various researchers in different contexts, such as online shopping (Hasbullah et al., 2016), recycling behaviours (Davis et al., 2002), and green buying behaviours (Ha and Janda, 2012).

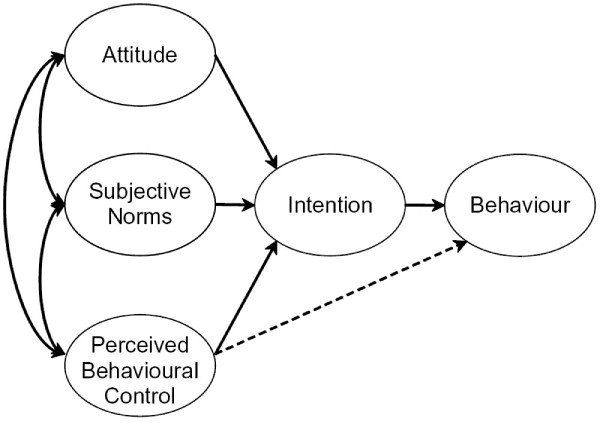

The Theory of Planed Behaviour (TPB) is an extension of The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen & Fishbein 1980). Both theories assume that an individual makes rational and reasoned decisions to perform a behaviour, by assessing the resources and information they have. However, TRA is criticized by mainly focusing on volitional determinants when examining the formation of an intention (Ajzen, 1985; Tu and Hu, 2018). Since a behaviour is not always voluntary nor can be controlled. Therefore, Ajzen (1991) has added perceived behavioural control to the model (see Figure 8). Han et al. (2010) points out that TPB “allows us to examine the influence of personal determinants and social surroundings as well as non-volitional determinants on intention” (p.326). This theory considers both internal (i.e. personal) and external (i.e. social) factors for one’s behavioral intention. Ajzen (1991) divides attitude and perceived behavioural control as personal factors, while subjective norms as social factors. It shows that TPB as a conceptual framework may be more comprehensive in identifying individuals’ behavioural intentions.

TPB has been widely applied in the context of green purchase intention and behaviour (Han et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2013; Chen and Tung, 2014; Paul et al., 2016). Similarly, this theory has been applied by various researches to examine the factors influencing consumers’ decisions of sustainable fashion. For instance, Lang and Armstrong (2018) suggest that a strong relationship between personal traits and intention for renting clothes is found. Tu and Hu (2018) propose that attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control positively influence the intention for renting clothes. McNeill and Venter (2019) point out that social and ethical implications of sustainable consumption behaviours are the weakest influencers for sustainable fashion consumption, such as clothing renting, swapping or sharing.

Figure 3.1 below shows The Theory of Planed Behaviour assumes attitude towards a behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control as the three and joint predictors of behavioural intention.

Figure 3.1: The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

(Source: Ajzen, 1991)

3.3.1 Attitudes

Kotler et al. (2016) define attitude as “a person’s enduring favourable or unfavourable evaluation, emotional feeling, and action tendencies towards some object or idea” (p.882). An object can be tangible or intangible. Attitude is an important research topic in the marketing field. As Chan and Cui (2002) point out that consumers’ satisfaction with product, pricing and service is associated with positive attitudes.

As shown in Figure 6, the first determinant of the theory is attitude toward behaviour. Ajzen (1991) defines attitude toward behaviour as “the degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation or appraisal of the behaviour in question” (p.188). An attitude can be positive, negative or neutral. According to the theory, one’s attitude toward a behaviour is affected by two factors. Firstly, the beliefs of the consequence of the behaviour. Secondly, the assessment of the possible consequence. Various studies also reveal that one of the main significant predictors of behavioural intention is attitude in the contexts of functional foods (Patch et al., 2005; Hung et al., 2016) and animal protection (Kotchen and Reiling, 2000). These are conforming to the findings from Chen and Tung (2014). The authors suggest that attitude is the psychological emotion resulted from consumers’ assessment. Positive attitude is likely to lead to positive behavioural intentions.

Study from Edbring et al. (2016) indicate that consumers’ attitude towards renting products tend to be positive. More specifically in the context of rental fashion, previous studies point out that a positive relationship between attitude and behavioural intention is established in different countries and cultures (Johnson et al., 2016; Lang, 2018; Tu and Hu, 2018; Lee and Chow, 2020). For instance, research from Johnson et al. (2016) reveals that attitudes towards online apparel collaborative consumption as a strong predictors of consumers’ behavioural intentions in the US, which is in line with the research by Lee and Chow (2020). Tu and Hu (2018) point out that attitudes of consumers’ in Taiwan positively influence their intentions to use online rental fashion platforms.

3.3.2 Subjective norms

Subjective norms are affected by the expectations and beliefs of other individuals. According to Ajzen (1991), subjective norm is defined as “the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform a behaviour” (p.188). It is the impact from important people or groups on an individual when he/she performs a specific behaviour. According to Ham et al. (2015), subjective norms refer to “the belief that an important person or group of people will approve and support a particular behaviour” (p.740). Ajzen (1991) refers these important people or groups as a reference group. Rivis and Sheeran (2003) point out that subjective norms are determined by the beliefs of significant others. Hee (2000) has featured these significant others as close friends, relatives, colleagues, or business partners. In other words, social influence, i.e. word-of-mouth from family members, friends and colleagues, can be one of the key factors affecting an individual’s intention to behave.

In the marketing and consumer behaviour context, different researchers point out that subjective norms have positively led to green buying behaviours (Lee, 2008; Ham et al., 2015; Khare, 2015), and intentions for purchasing online (Hasbullah et al., 2016). In the context of rental fashion, subjective norms accentuate the impacts of others’ opinions on the intentions to rent fashion items. As discussed previously in section 1.3 on rental fashion in the UK, UK consumers are not familiar with the concept of rental fashion. Referring to Schepers and Wetzels (2007), when consumers lack previous experience of renting clothes, they may tend to seek recommendations and information from those who are in their social circle. Therefore, subjective norms may play an important role in decision making.

3.3.3 Perceived behavioural control

As defined by Ajzen (1991), perceived behavioural control refers to “people’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour of interest” (p.183). In other words, it is an individual’s perception of his/her capability to perform a behaviour (Mathieson, 1991). Ajzen (1991) points out that perceived behavioural control acts as a significant factor of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. As it is also the refection of an individual’s past experiences and foreseen difficulties. Zhou et al. (2013) point out that one’s motive and ability (i.e. behavioural control) as the influencers of a behaviour. There are two determinants influencing perceived behavioural control, the first one as self-efficacy, the second one as resource facilitating conditions (Taylor and Todd, 1995; Zolait, 2014). According to Bandura (1991), self-efficacy beliefs have an effect on the preparation and choice of activities, patterns of thinking and emotional reactions. Bandura (1992) defines self-efficacy as “individual judgements of a person’s capabilities to perform a behaviour”, as cited in Paul et al. (2016). Taylor and Todd (1995) state that resource facilitating conditions as the availability of resources, such as time and money.

Various studies have also shown a positive relationship between perceived behavioural control and intention in green purchase behaviour (Han et al, 2010; Paul et al., 2016), and rental fashion Lang and Armstrong, 2018; Tu and Hu, 2018).

3.4 Perceived risks towards rental fashion

Bauer (1960) was the first researcher to introduce the concept of perceived risk, as cited in Kang and Kim (2013). The author defines perceived risk which consists of the likelihood of financial loss, unhappiness, lack of anticipated effectiveness, physical damage, or negative social image. Schiffman and Wisenblit (2018) have summarized perceived risks as “the uncertainty that consumers face when they cannot foresee the consequences of their purchase decisions.” (p.135). The authors point out that perceived risks to be divided into functional, physical, financial, psychological, social, and time risks. Rogers (1995) states that perceived risk act as a significant role in preventing an individual from accepting innovative and new products. Based on the study conducted by Gifford and Bernard (2006), products associate with a high level of uncertainty lead higher perceived risks. As during a decision-making process which involves high risks, an individual tends to prevent from making mistakes (Liao et al., 2010). UK consumers tend to not rent clothes. Perceived risks in rental fashion may include the clothing quality, price, or hygiene issues. It is important to examine the perceived risks in the context of rental fashion. As perceived risks may affect consumers’ decisions.

3.4.1 Financial risk

Kang and Kim (2013) identified financial risk as the “concerns about potential monetary and economic loss, which hinges upon the price of the focal product” (p.269). Schiffman and Wisenblit (2018) define financial risk as “product will not be worth its cost” (p.136). Lu et al. (2005) suggest that if the same product being cheaper in other places is also a financial risk. Moreover, financial risk also includes the possibility of not receiving the product after the payment transactions (Biswas and Biswas, 2004).

Although rental fashion services offer a more sustainable and affordable option to consumers, Armstrong et al. (2015) indicate that one main concern over rental fashion is financial issues. Recent researches have also pointed out that financial risk negatively influenced an individual’s attitude towards environmentally sustainable apparel consumption (Kang and Kim, 2013; Lang, 2018). For instance, consumers may think paying for renting but not owning a fashion item is a waste of money. Or consumers may worry what they spend is only for a short time of utility. It is supported by the study conducted by Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012). The authors denote that rental fashion services may encourage more temporary consumptions, thus consumers may spend more to rent clothes at the end.

3.4.2 Performance risk

Performance risk and functional risk are in common use. As defined by Kang and Kim (2013), performance risk is also regarded as quality risk. According to Schiffman and Kanuk (2004), the failure of a shopper’s ability to judge the quality of the product may lead to performance risk. Consumers may also lack trust in rental service providers. Armstrong et al. (2015) suggested that continuation of business, durability, size and quality issues, and concerns over hygiene be the trust issues. For instance, Chan (2020), journalist from fashion magazine Vogue, suggests that the current Covid-19 pandemic has led to concerns over hygiene issues of rental fashion industry. Recent studies also reveal that consumers may question about the cleanliness and quality of the rented items (Lang, 2018; Gumulya and Ginting, 2020). As the rented items are being shared and used. A negative relationship between performance risk and online shopping behaviour (Ariff et al., 2014) and renting fashion items (Lang, 2018) is found.

3.4.3 Psychological risk

As identified by Kang and Kim (2013), psychological risk refers to “possible damage to one’s self-image” (p.269). According to Ueltschy et al. (2004), psychological risk refers to an individual’s let-down in oneself resulted from disappointing choices of a product or service. Fashion can be linked to one’s identity, personality, status, or self-image. Gonzalez and Bovone (2012) suggest that fashion is associated with a sense of belonging, and a recognition from a specific status group. Roach-Higgins and Eicher (1992) state that fashion or clothes can be used as a way an individual communicates and expresses his/her identity. A recent research by McNeill (2018) finds out that women viewing their clothes “as a representation of self” (p.90). Moreover, clothing allows them to show their personalities. These show that consumers purchase and own a particular fashion item in order to define and present who they are.

However, Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012) point out that renting behaviours may be perceived as having a low social status and low financial power. According to Kang and Kim (2013), an individual may have concern over a discrepancy between self-image and environmentally sustainable apparel products. The feeling of unfamiliarity and awkwardness may be formed. Lang (2018) suggests that consumers may worry about if the rented clothes match their personal image or style. Therefore, a negative relationship between psychological risks and consumers’ attitudes towards rental services is resulted (Kang and Kim, 2013; Lang, 2018; Gumulya and Ginting, 2020).

3.4.4 Social risk

Defined by Schaefers et al. (2016), social risk refers to “the extent to which purchase decisions are believed to be judged by others and may influence one’s social standing” (p.572). Kang and Kim (2013) point out that social risk can be easily confused with psychological risk. Chen and Chang (2005) have stressed that social risk is about how the use of a product may harm one’s image in the eyes of others. Therefore, it is determined by how others or the society impact one’s decisions. Study by Trocchia and Beatty (2003) proposes that, it is more inclined for consumers who choose access-based consumption over ownership to strive for social consent.

However, research by Armstrong et al. (2015) shows that social risk as a significant concern over rental fashion. Since fashion trends change frequently, consumers may worry rented items are not trendy enough (Kang and Kim, 2013; Lang, 2018). Moreover, consumers may also concern about how others view their renting behaviour (Gumulya and Ginting, 2020). Studies show that social risk negatively impacts attitudes towards different activities such as renting clothes (Kang and Kim, 2013), and shopping online (Gerber et al., 2014).

3.5 Summary

As outlined in the chapter, this research is adopting The Theory of Planned Behaviour as the framework to examine the intention of renting fashion items. Regarding the construct of attitude, literature has shown perceived risk to have a negative relationship with attitude. Since most of the previous studies regarding rental fashion are conducted without UK, therefore further investigation is needed regarding the British market.

Chapter Three – Conceptual Development

4.1 Introduction

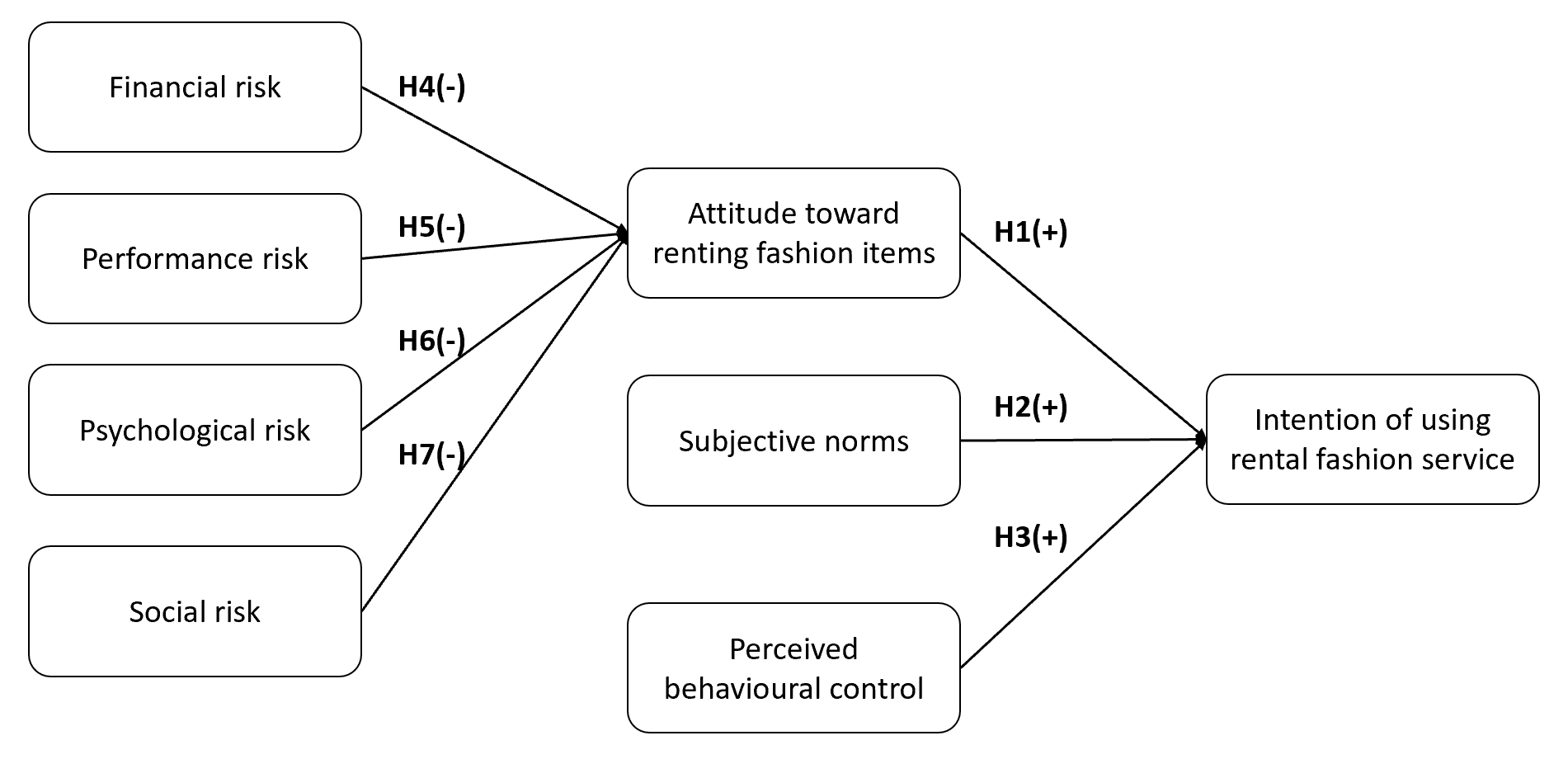

Based on the literature review, a conceptual framework will be developed in this chapter as a direction and guideline of this research. This framework will combine the variables in The Theory of Planned Behaviour, and four types of perceived risk identified in Chapter Two (i.e. financial, performance, psychological and social risks).

4.2 Relationship between attitude and behavioural intention

4.3 Relationship between subjective norms and behavioural intention

4.4 Relationship between perceived behavioural control and behavioual intention

4.5 Financial risk and attitude

4.6 Performance risk and attitude

4.7 Psychological risk and attitude

4.8 Social risk and attitude

4.9 Summary

The Theory of Planned Behaviour will be applied as a framework for this research, in order to examine consumers’ behavioural intention of renting fashion items. According to the theory, there are three antecedents, namely attitude towards a behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. According to Tu and Hu (2018), a behavioural intention refers to an individual’s propensity if he/she would like to perform a specific behaviour. Behavioural intention can be determined by the eagerness of an individual to try to perform the behaviour. Ajzen (1985; 2002) proposes that behavioural intention as the ideal way to predict a behaviour. Therefore, it is assumed that a greater behavioural intention will lead to a higher opportunity of an individual to perform that behaviour.

Ajzen (1991) points out that attitude toward behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control as strong predictors of behavioural intentions. The Theory of Planned Behaviour have been widely applied in the contexts of green purchase and renting behaviours (Han et al., 2010, Zhou et al., 2013; Chen and Tung, 2014; Ham et al., 2015; Paul et al., 2016; Lang and Armstrong, 2018; Tu and Hu, 2018). Studies also demonstrate that attitude toward behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control positively influence behavioural intention (Han et al., 2010; Ham et al., 2015; Tu and Hu, 2018). Therefore, this study also assumes that attitude toward behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control will positively influence UK consumers’ intentions to rent fashion items. Thus, the below hypotheses are proposed.

H1: Attitude toward rental fashion positively influence consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items.

H2: Subjective norms positively influence consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items.

H3: Perceived behavioural control positively influences consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items.

3.3 Perceived risks and attitude

Various studies have shown attitude as a strong predictor of behavioural intention (Patch et al., 2005; Kotchen and Reiling, 2000; Hung et al., 2016). According to Maccketti and Shelley (2009), an attitude toward behaviour is a more significant predictor than subjective norms in behavioural intention. In order to understand consumers’ barriers or hesitations of renting fashion items, researchers have investigated the perceived risks of renting behaviours. According to Schiffman and Wisenblit (2018), perceived risks are divided into six types as financial, functional (or performance), psychological, social, physical and time. Rental fashion mainly involves the risks of financial, performance, psychological and social. In the context of renting behaviours, various studies have shown a negative correlation between these four risks and attitude (Kang and Kim, 2013, Lang, 2018; Gumulya and Ginting, 2020). Kang and Kim (2018) also point out that attitude as an important mediator between perceived risks and behavioural intentions. Therefore, this study assumes that financial, performance, psychological and social risks will have a negative impact on UK consumers’ attitude toward renting fashion items. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed for this study.

H4: Financial risk of renting fashion items negatively influences consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services.

H5: Performance risk of renting fashion items negatively influences consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services.

H6: Psychological risk of renting fashion items negatively influences consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services.

H7: Social risk of renting fashion items negatively influences consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services.

Based on the above proposed hypotheses, the following conceptual is suggested for the study. The framework has combined The Theory of Planned Behaviour and the four perceived risks involving in renting fashion items. It also shows the relationship among the variables.

Figure 4.1: Conceptual framework

3.4 Summary

As outlined in this chapter, the findings of previous literature reviews have been summarized. By combining The Theory of Planned Behaviour and the findings, a conceptual framework of this study is developed. The hypotheses proposed are also in line with the research aim of this study.

Chapter Four – Methodology

5.1 Introduction

This chapter encompasses the methodology that was applied in gathering information for the research. Thus, it describes the selected methods, process of research, collection of data, and approaches used as well as strategies in the research. Similarly, it provides in-depth decryption of the processes used in the analysis of data for the research. (mention pilot test)

5.2 Research philosophy

According to Easterby-Smith et al. (1999), research philosophy is significant and useful in deciding the selection of research design and why. Collis and Hussey (2003) divide research paradigms into the positivistic paradigm and the interpretivist paradigm. The authors define a research paradigm as people’s beliefs and assumptions about the world, and the research design and procedures will be influenced.

According to Saunders et al. (2019), research philosophy is the first layer of the research process, which connects to the nature and development of knowledge. Al-Ababnch (2020) states that researchers choose the research methodology based on the philosophical issues, which are associated with ontology (the nature of reality) and epistemology (the nature of knowledge).

5.2.1 Ontology

According to Saunders et al. (2019), ontology refers to the “assumptions about the nature of reality” (p.133). Al-Ababnch (2020) states that realism is “based on the belief that reality exists in the world, and this reality is independent of human thoughts and beliefs” (p.81). A scientific approach is assumed for the establishment of knowledge. According to Sobh and Perry (2006), the philosophical position of realism is that the reality exists independently, and a realism research aims at understanding “the common reality of an economic system in which many people operate inter-dependently” (p.1200). Based on the objectives of this research, relative realism is followed. According to Mizrahi (2013), relative realism is about to get closer to the truth, and comparative theory evaluation. It is a combination of realist and antirealist.

(one sentence link to this research)

5.2.2 Epistemology

Positivism and interpretivism are two opposite theoretical perspectives. According to Saunders et al. (2019), positivism “promises unambiguous and accurate knowledge” (p.144). Al-Ababnch (2020) states that positivism relies on direct experience but not speculation. Whereas, interpretivism stresses that individuals create meanings, so they are different from physical phenomena (Saunders et al., 2019). Remenyi et al. (2005) indicate that interpretivist philosophy emphasizes a subjective and descriptive method.

Based on the research aim and objectives of this research, positivist approach is followed. Crotty (1998) points out that positivism adopts the ways of natural science through value-free, detached observation, and recognizing the characteristics of human-hood, society and history. According to Dudovskiy (2018), positivism usually consists of the application of existing theory to develop hypotheses, and hypotheses testing. As shown in the previous chapter on conceptual development, a conceptual framework and hypotheses are set up based on existing marketing theory. Also, this research progresses through hypotheses and deductions, and generalisation through statistical probability, with a large number of population sampling being selected (Ramanathan, 2008).

5.3 Research approach

There are two types of research approaches, namely deductive and inductive. According to Saunders et al. (2019), a deductive approach is used when a research aims at developing theories and hypotheses, as well as hypotheses testing. It is associated with positivist philosophy. While an inductive approach is used when the outcome of data analysis is to establish a theory. It is associated with interpretivist philosophy. Since positivism is followed as epistemology of the research, a deductive research approach is adopted. Creswell and Clark (2017) state that a deductive approach is a top-down approach, which is from theory to data. This research is built on existing literature.

5.4 Research strategy

Saunders et al. (2019) indicate that the research question and objective, research philosophy and the scope of current knowledge will determine the selection of research strategy. Quantitative and qualitative methodologies are the two main types of research methodology. According to Al-Ababnch (2020), quantitative methodology is grounded on positivist paradigm, and aims at surveying the social phenomena by gathering and analysing data. On the other hand, qualitative methodology is grounded on interpretivist paradigm, and aims at learning the meaning of social phenomena. (add a bit more)

(stronger link to objective)

This research aims at examining consumers’ perceptions of rental fashion and the perceived risks involved. A quantitative research approach is applied as knowledge will be generated by “investigating things which we could measure in some way” (Al-Ababnch, 2020, p.76). Moreover, since there is a limited time to collect the data, therefore, a quantitative approach will be more beneficial for this research. As Daniel (2016) suggests that a quantitative research approach is more time and resources-saving, as well as data from a relatively larger population can be generated.

5.5 Research design

A descriptive approach is followed as this study aims at describing market characteristics or functions and built on previous formulation of specific hypotheses (Malhotra, 2019). Also, according to Swatzell and Jennings (2007), descriptive statistics “help simplify large number amount of data in a sensible way”.

This research follows a cross-sectional design. According to Al-Ababneh (2020), cross-sectional approach is a positivistic methodology. This approach allows researcher to examine the relationships among variables in large samples. Malhotra (2019) points out that data and information will be collected only once from the given sample of population elements by applying cross-sectional approach.

5.6 Data collection

In a quantitative research strategy, an online survey is used in order to collect the data. According to Rowley (2014), survey is a simpler way to collect responses from a large number of populations, and the findings generated from the data can be more generalisable. 200 responses are expected for the analysis. According to Saunders et al. (2019), a survey strategy links to deductive approach and is perceived as positivistic methodology.

5.7 Sampling (extend this part) (accessibility, purposes sampling)

Non-probability sampling is applied.

5.8 Questionnaire design

Closed-ended questions including yes/no questions, multiple choice, and scaled questions will be used for the questionnaire design. According to Roopa and Rani (2012), questions should be simple, accurate, easily understood by the participants, and avoiding words with ambiguous meanings or emotional connotations. (each question only test one variable)

5.8.1 Pilot test (mention method)

A pilot test is conducted and tested among ten participants. Rowley (2014) points out that a pilot test helps to examine if the questions are forthright and easy for participants to understand and complete. Also, according to Baker and Foy (2008), both the questions (i.e. the variation, meaning and difficulty); and the questionnaire (i.e. the question order, timing, and respondent interest) are tested. Any problems appeared from the pilot test have been eliminated and questions have been modified.

5.9 Reliability and validity (extend this section/different layers)

In order to test the consistency of the results of the research, Cronbach’s alpha will be measured for each of the variables. According to Omillo-Okuma (2020), Cronbach’s alpha shows the level of inter-item correlation and their relatedness. The Cronbach’s alpha falls between the value of 0 and 1. As suggested by DeVellis (2012), a Cronbach’s alpha value between 0.7 and 0.8 is perceived as respectable. Therefore, this research has followed this guideline and adopts if the value is ≥ 0.7. Also, previous studies have used Cronbach’s alpha α especially for questionnaires aimed at determining factors in the affective domains, such as attitude, and motivation (Tuan et al., 2005; Eilam and Reiter, 2014). In order to measure the accuracy of the research results, content validity will be followed by comparing the results from this research with literature review. Questions using in the survey are adapted from previous literature review (see Appendix 1).

5.10 Ethical considerations

Kaewkungwal and Adams (2019) suggest that risk/benefit, vulnerability and confidentiality/privacy are the main three ethical considerations of conducting a research. Since an online survey is used to collect data for this research, Bryman and Bell (2007) point out that full agreement from the participants should be gained before the research. The aims and objectives of the research should be clearly communicated with the participants. Also, Bryman and Bell (2007) have added that the anonymity of the participants should be assured, and a high level of confidentiality and protection of participants’ privacy should be guaranteed.

(mention the steps taken in this research)

5.11 Summary

This chapter has presented the methodology adopted in this research. As mentioned in Chapter Three on conceptual development, this research aims at examining the relationships between different variables and testing hypotheses. Therefore, a deductive approach and survey strategy are applied. After collecting the data, the findings and analysis will be discussed in the next chapter.

Chapter Five – Empirical findings

6.1 Introduction

The focus of the analysis is to examine the perceptions and attitudes of the consumers to rental fashion in the UK and the potential risks involved. Therefore, the analysis of data showcases the fundamental issues captured in the study’s objectives at the same time test the proposed hypotheses.

6.2 Data Screening

Cronbach’s Alpha is going to be executed to ascertain the reliability of the survey used to achieve the objectives in the review. The results are as shown below under table 6.1.

| Reliability Statistics | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

| .733 | 26 |

Table 6.1: Cronbach Alpha test results

Source: (Author, 2020)

The Cronbach’s Alpha rests at .773 meaning the dataset used in the study as generated in the survey is reliable at 77.3%; this is a good sign that the survey data is reliable in addressing the issues sought.

6.3 Descriptive analysis

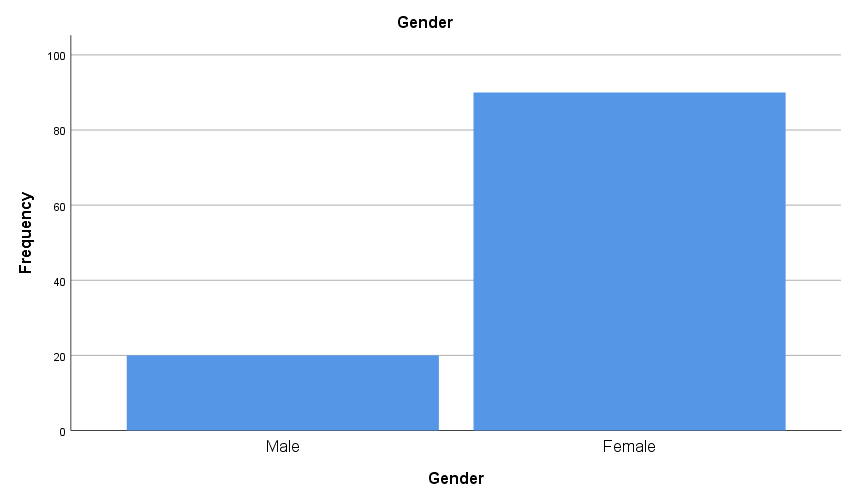

The demographic aspects of the participants are reported in this section: foremost, the results indicate that 18.2% of the participants are males while 81.8% are females. The same results are captured in figure 1 below using a graphical model whereby females have the highest frequency meaning they are more in the sample.

Figure 1: Gender

Source: (Author, 2020)

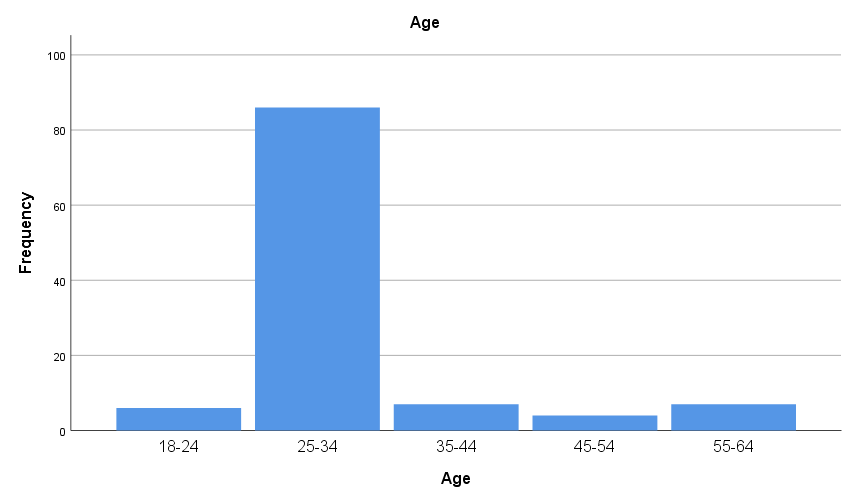

In terms of age, 5.5% of the participants are in the age-bracket 18-24 while the largest portion at 78.2% falling at 25-34 years. Then, 6.4% are in the age bracket 35-44 while 3.6% being 45-54 years. Figure 2 below captures the same graphically where the group at 25-34 years is the highest frequency.

Figure 2: Age

Source: (Author, 2020)

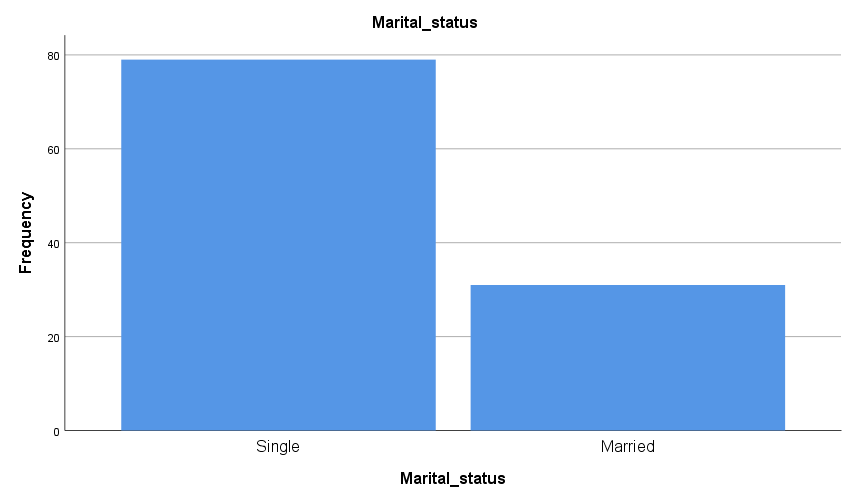

Further review indicates that 71.8% of the participants are single while 28.2% are married. Figure 3 below illustrates the same trend using a pie chart where the large portion shows to be individuals that are single.

Figure 3: Marital Status

Source: (Author, 2020)

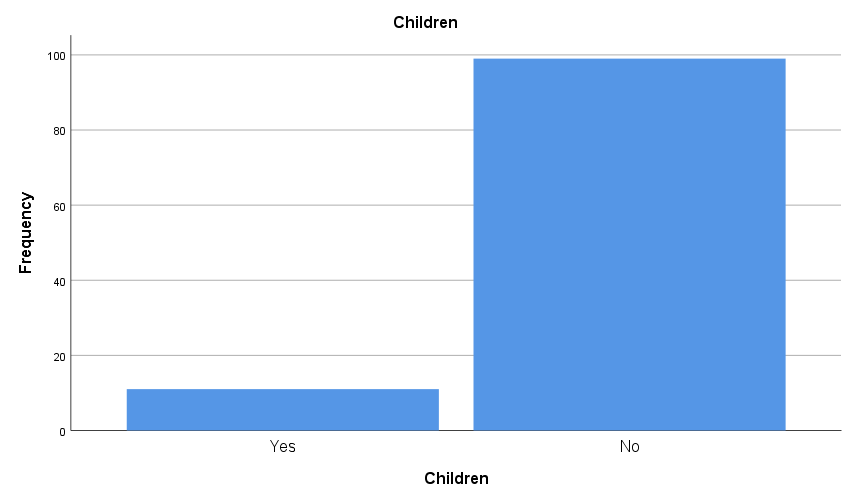

Another demographic review indicated that 10% of the participants reported to have children while 90% said they did not. Figure 4 below shows that the greatest portion of the participant was that without children.

Figure 4: Children

Source: (Author, 2020)

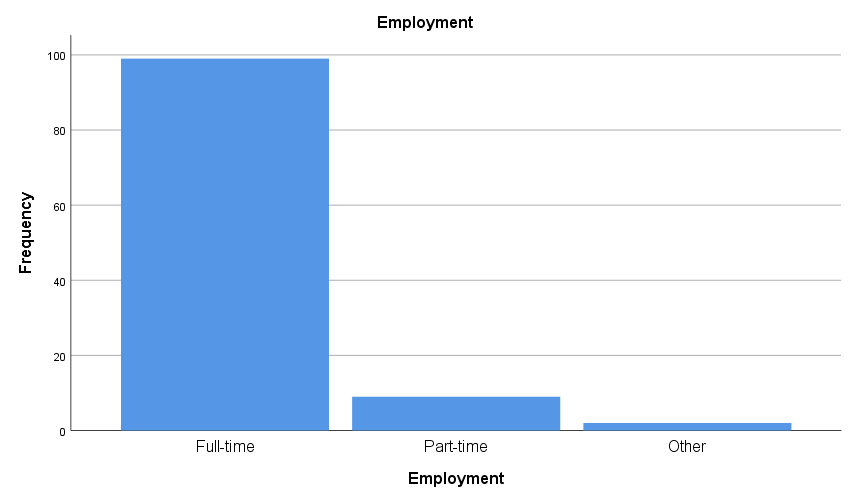

The other demographic review was about employment whereby 90% of the sampled group indicated to work full-time while 8.2% were enrolled as part-timers while 1.8% was in other category of employment. As shown in figure 5 below the modal sample was taking part in full-time employment.

Figure 5: Employment

Source: (Author, 2020)

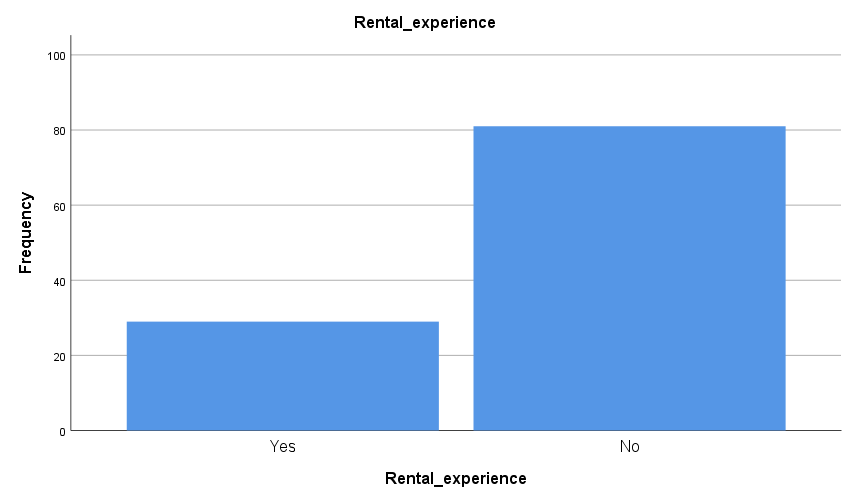

In addition, 26.4% of the participants depicted to have rental experience while 73.6% said no while figure 6 presents similar results.

Figure 6: Rental Experience

Source: (Author, 2020)

6.4 Attitudes, Social Norms, and Perceived Behavioural Control

The outlook for attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioural control is going to be captured using summary statistics presented in Appendix 2. The indications are that all the trends have a standard deviation that is below the mean which indicates that the agreement to each of the issues by the participants is consistent and stable. In point of fact, the minimum response at 1.00 is depiction of the presence of strongly disagreed response while 5.00 being strongly agreed response. Overall, the outlook on attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioural control shows an indication where there are neutral and agreed responses with the matter in question.

With this above been said, the next review is to establish whether there is any correlation across the variables as modelled in Appendix 3 using Pearson Product Moment Correlation. The outlook shows that a high majority of the cases return a positive and strong correlation that is significant at 95% confidence interval. For that case, attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioural control trends can be confirmed to have supported relationship as well as interconnectivity. The researcher further considers this outcome as an essential assumption ahead of the implementation of regression models.

6.5 Perceived Risks which Prevent UK Consumers from Renting Fashion Items

The trend results for the perceived risks preventing UK consumers from renting fashion items are as presented in appendix 4. Foremost, the central tendency metrics i.e. mean and standard deviation depict that all the cases representing perceived risks are consistent and stable since the standard deviations are below the mean performance. Moreover, on the average the respondents were neutral about the matters in question although at the minimum there are those that strongly disagreed; while at the maximum, there are strong agreements with the issues raised about perceived risks. Then, appendix 5 captures the correlation of the same variables representing perceived risks. Throughout the review, it is evident that there are high cases of positive and significant linearity among the variables; the same affirms the presence of interconnectedness in the patterns underlying each of the perceived risks that prevent UK consumers from renting fashion items. Moreover, the presence of correlation is an important assumption for executing regression analysis in due course of the study.

6.6 Intention to Use Rental Fashion Service

The feedback on the intention to use rental fashion service served as the predicted variable measured using three phenomena as shown in Appendix 6 summary results. For instance, all the dispersion rates are showing to be lower than the average scores meaning there is consistency and stability in the sense in which the participants remained neutral about the issues in question. The affirmation is that in the minimum the respondents disagreed while in the maximum they strongly agreed with the concerns around the intentions to use rental fashion service. Therefore, the study deduced that the participants would neither agree nor disagree to consider renting fashion items in the future; that they would consider switching their habit from buying to renting fashion items; and lastly, they intended to rent fashion items in the future.

6.7 Test of Significance

The study’s hypotheses are going to be examined in this section with the rejection of the null hypothesis based on decision rule for 5% margin of error or 95% confidence interval. For instance, H1-H3 has been addressed using Hierarchical Regression presented in appendix 7. The model specification is as follows:

FI = α + β1AT + β2SN + β3PBC + e ……………………………………………………… (1)

First, the model summary proves that there exists a goodness-of-fit in the variables representing attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control since 55.3% to 59.4% are the cases of the predictor variables that explain consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items. Moreover, the entire model is significant since the ANOVA (F = 14.469, Sig. = .000) is below 5% margin of error hence the predictor variables are important in influencing the outcome of the regression. Then, the actual model parameters further indicate that SN1 (β = .288, Sig. = .018), PBC2 (β = .294, Sig. = .000), and PBC5 (β = .402, Sig. = .000) while none of the cases for attitudes shows to have any influence on consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items. In this regard, the researcher deduced as follows: H1 is rejected while H2 and H3 are not rejected. The entire hierarchical regression is without bias or problems of multicollinearity hence can be used to make further decisions at managerial or professional context.

Secondly, the other model is going to be implemented using Hierarchical Regression and aimed to address H4-H7. The model sought is as expressed below while Appendix 8 has captured the results of the regression.

FI = α + β1FR+ β2PR + β3PSR + β4SR + e ……………………………………………. (2)

In context of the results shown under Appendix 8 the relationship between consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services as the explained variable and the predictors variables constituting the perceived risks which prevent UK consumers from renting fashion items. Foremost, the model summary based on the adjusted R2 and R2 depicts that 20.4% to 29.9% of the cases for perceived risk explain consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items; for this, the researcher would consider a weak goodness-of-fit. In addition, the ANOVA (F = 3.145, Sig. = .001) further depicts that the entire model is statistically significant meaning the influence of the different levels of perceived risk towards the predicted variable in the model cannot be regarded to be mere coincidence. The alpha coefficient (β = 3.720, Sig. = .000) shows that without the influence of the various aspects of perceived risk there would still be recorded some consumer behavioural intentions to use rented fashion items. The actual model parameters indicate that FR1 (β = .271, Sig. = .041), PSR1 (β = -.269, Sig. = .042), and SR1 (β = -.414, Sig. = .016) are the predictor variables whose beta values are below the 5% margin of error. In that case, they have significant predictive effects on consumer behavioural intentions to rent fashion items although PSR1 and SR1 would decrease it with 26.9% and 41.4% respectively. Thus, from the results above the following can be deduced: H4, H6, and H7 cannot be rejected while H5 is hereby rejected.

6.8 Discussion

The focus of the analysis has been to establish the interconnectedness between: (a) attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioural control of UK consumers and (b) perceived risks which prevent UK consumers from renting fashion items. Throughout the model analysis it has been shown that the influence of the mentioned factors is significant towards consumer behavioural intentions to use rental fashion services. The same affirmations are present in the research by Han et al. (2010); Ham et al. (2015); Tu and Hu (2018); by implications it means that the marketing initiatives to promote rental fashion services should be taking into account the attitudes, social norms, perceived behavioural control, and the perceived risks of the consumers.

In the results it was evidenced that attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioural control have higher influence towards consumer behavioural intentions towards rented fashion service and this confirms the studies by Han et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2013; Chen and Tung, 2014; Ham et al., 2015; Paul et al., 2016; Lang and Armstrong, 2018; Tu and Hu, 2018. Nonetheless, attitudes proved to have no significant predictive effects on the intentions to use rental fashion services failing to support the works by Kang and Kim (2013). The fact of perceived risk having significant predictive effects on consumption of rental fashion services aligned to the findings by Kang and Kim (2013); Gumulya and Ginting (2020). Although, it can be recalled that social risk and psychological risk both returned negative beta values. For that reason, indicating that they reduce the intentions around buying or utilising rental fashion items. The same outcomes are supported in the works by Lang (2018). In this case, the findings validated the model that perceived risks cum attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control are significant in developing a model that can be used to increase purchase intentions of the UK consumers towards rental fashion. On the other hand, perceived risks excluding performance risk are other facets that can be used to influence consumption or positive intentions around the use of rental fashion items. In this case, the model may be validated and used in the marketing realm to propagate for the success of increased sales for rental fashion items or commodities in the UK market.

In summary the study’s hypotheses yielded the following results:

| Hypothesis | Expected Outcome | Actual Outcome |

| H1: Attitude toward rental fashion positively influences consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items. | Not Rejected | Rejected |

| H2: Subjective norms positively influence consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items | Not Rejected | Not Rejected |

| H3: Perceived behavioural control positively influences consumers’ behavioural intentions to rent fashion items | Not Rejected | Not Rejected |

| H4: Financial risk of renting fashion items negatively influences consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services | Not Rejected | Rejected due to the positive beta |

| H5: Performance risk of renting fashion items negatively influences consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services | Not Rejected | Rejected |

| H6: Psychological risk of renting fashion items negatively influences consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services | Not Rejected | Not Rejected |

| H7: Social risk of renting fashion items negatively influences consumers’ attitudes towards rental fashion services | Not Rejected | Not Rejected |

Table 1: Hypothesis test results summary

6.9 Summary

Chapter Six – Conclusion and Recommendations

7.1 Effective Summary/Overview

The sharing economy in contemporary times has become more evident in accommodation, travel, food, and, most recently, fashion. In the fashion industry, consumers are replacing the notion of buying with renting. Based on its nature, consumers agree that renting offers the latest fashion at a price that is relatively low compared to buying, making it attractive. The key reason for continued growth in fashion renting, as shown by Clube and Tennant (2020) is the change in consumer perceptions. Compared to traditional fashion industry, consumption patterns in fashion renting brings out a different kind of consumption. Cavender et al. (2020) has shown there is a need by consumers to wait, for luxury clothes, for their chance to wear such clothes in cases where they are limited. However, several barriers have been associated with rental fashion among them being increased waiting time and lack of availability, which requires changes in the current shopping behaviour of consumers (Brydges et al., 2018). The other barriers with rental fashion are that consumers have to ensure clothes are in good condition when they are returned, based on the agreed time, and that clothing ownership is a collective experience rather than an individual experience.

7.2 Summary of key findings

From the study’s results, it has been established that attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control have higher influence towards consumer behavioral intentions towards rented fashion service. This is confirmed by Han et al., 2010; Tu and Hu, 2018. However, no significant consumption predictive effects on the intentions to use rental fashion services were associated with attitudes. Contrary, as seen in the findings by Kang and Kim (2013) and Gumulya and Ginting (2020), the study revealed that perceived risk had significant predictive effects on consumption of rental fashion services. On social risk and psychological risk, the findings have validated the model that perceived risks cum attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control are significant in developing a model that can be used to increase purchase intentions among UK consumers with respect to rental fashion. With the exception of performance risk, perceived risk is another facet that influences positive intentions or consumption surrounding the use of rental fashion items. On the other hand, financial and performance risks yielded not positive influence on consumer attitudes towards rental fashion services. The findings have been validated and are used in the marketing realm to propagate success of increased sales for rental fashion items or commodities in the UK market.

7.3 Management recommendations by adopting the AIDA model

It is essential for the rental fashion industry in the UK to gain awareness and generate sales and doing this requires effective use of the AIDA model. Using the awareness portion of the AIDA model, management in the rental fashion in the UK should focus on getting their business out for potential consumers to see. To accomplish this, the management will have to engage in advertising campaign through various platforms like company’s social media, websites or even blogs (Hassan et al., 2015). This will ensure rental fashion awareness among consumers making them consider doing business with rental fashion companies. Using the interest portion of the AIDA model, management should work to ensure they grab the interest of the consumer. Once attention has been gained, the organization has to offer somethings that generates real interest in potential consumers enabling them to consider renting fashion clothes (Pashootanizadeh, & Khalilian, 2018). Management will therefore have to ensure wants or needs of consumers with regards to rental fashion have been identified and met. Using the desire portion of the AIDA model, management will have to ensure the gained interest on rental fashion has created a desire, in the consumer, to become an actual consumer. To achieve this, management must ensure potential consumers see the benefits they stand to gain through rental fashion consumption (Cheah et al., 2019). Thus, more advertising has to be engaged to convince consumers. The action portion of the AIDA model is to ensure consumers rent fashion clothes. From an online perspective, management has to make sure that consumers have plenty of conversion chances for the consumer to have several opportunities to rent that desired fashion clothe (Kotler et al., 2016).

7.4 Limitations and future research

While the research makes an illustration of the fashion industry, it particularly associates the trends in rental fashion to online consumption. This limits the research to the scope of online rental consumption and fails to incorporate walk in retail consumption on rental fashion. This brings about bias since there is no comparison being made to the perception that would have been generated from walk in rental consumers. Another limitation associates with the location of the study. Only UK rental fashion consumers are focused on and likewise, no comparison to other nations. For future research, researchers should ensure a broader perspective of the study by incorporating walk in retail consumers in their study towards the development of broader population. Incorporating findings from other nations will bring out a more informed understanding of rental fashion consumption as well as guide the industry on how to improve consumption from a globalized perception.

Needs help with similar assignment?

We are available 24x7 to deliver the best services and assignment ready within 3-4 hours? Order a custom-written, plagiarism-free paper